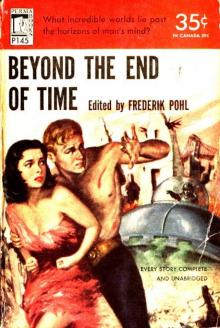

Beyond The End Of Time (v1.0)

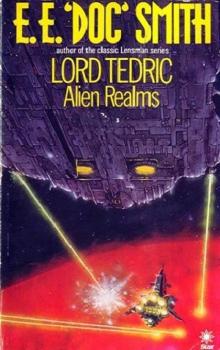

Beyond The End Of Time (v1.0) Alien Realms (v1.0)

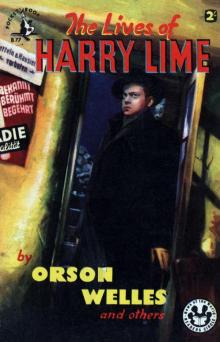

Alien Realms (v1.0) The Lives of Harry Lime v1.0

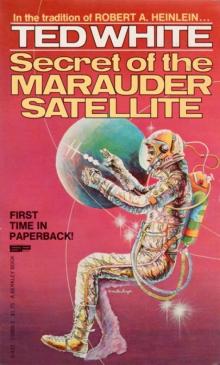

The Lives of Harry Lime v1.0 Sectret of The Marauder Satellite (v1.0)

Sectret of The Marauder Satellite (v1.0) chaos engine trilogy

chaos engine trilogy Untitled

Untitled Assignment Bangkok

Assignment Bangkok Assignment Afghan Dragon

Assignment Afghan Dragon spice&wolfv3

spice&wolfv3 Green Lantern - Sleepers Book 2

Green Lantern - Sleepers Book 2 Countdown

Countdown Alyx - Joanna Russ

Alyx - Joanna Russ Otto Penzler (ed) - Murder 06 - Murder on the Ropes raw

Otto Penzler (ed) - Murder 06 - Murder on the Ropes raw The Snow Garden

The Snow Garden Abominations

Abominations The Legacy Quest Trilogy

The Legacy Quest Trilogy Jack Faust - Michael Swanwick

Jack Faust - Michael Swanwick Friend or Foe

Friend or Foe path to conquest

path to conquest The Return

The Return Generation X - Genogoths

Generation X - Genogoths scott free

scott free The rivals of Sherlock Holmes : early detective stories

The rivals of Sherlock Holmes : early detective stories A Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to Wittgenstein, Second Edition

A Short History of Modern Philosophy: From Descartes to Wittgenstein, Second Edition Shadow of the Past

Shadow of the Past Generation X - Crossroads

Generation X - Crossroads Search and Rescue

Search and Rescue Demons

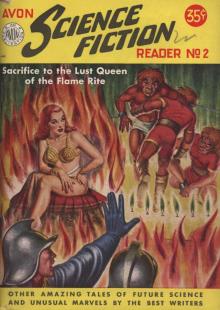

Demons Avon Science Fiction Reader 2

Avon Science Fiction Reader 2 Untitled.FR11

Untitled.FR11 On a Darkling Plain

On a Darkling Plain Legends

Legends The Jewels of Cyttorak

The Jewels of Cyttorak Choir Boy

Choir Boy iron pirate

iron pirate Cunning of the Mountain Man

Cunning of the Mountain Man GEN13 - Version 2.0

GEN13 - Version 2.0 Salvation

Salvation Psychohistorical Crisis

Psychohistorical Crisis a terrible beauty

a terrible beauty Soul Killer

Soul Killer Farmer, Philip José - Traitor to the Living

Farmer, Philip José - Traitor to the Living Law of the Jungle

Law of the Jungle The Mapmaker's War

The Mapmaker's War The Ultimate X-Men

The Ultimate X-Men Watcher

Watcher Pomegranates full and fine

Pomegranates full and fine Assignment Sorrento Siren

Assignment Sorrento Siren